"Invest For The Long Term"...In What?

/“Invest for the long term”

You’ve probably heard it before from the mouths of numerous financial aficionados. It sounds good doesn’t it. Whilst friends, family, colleagues and news anchors might try to put you in panic-mode (think late 2007), you know that short term volatility is expected but longer term gains are a given. Right? Well, not always.

This isn’t an article designed to fear-monger, it’s sole purpose is to enlighten and to answer the big question “invest for the long term yes…but in what?”

My investment decisions are exactly that, my own. As as UK-based investor, I based each investment decision on my own research. These are, by no means, investment recommendations. Before making any investment decision, you must do your own research and/or speak to a professional. For the full disclaimer, click here.

Contents

- What Is Long Term Investing?

- Long Term investing In Cash

- Long Term Investing In Single Stocks

- Long Term Investing In Index Funds

- - Which Index/Indices?

- - Other Indices

- - How To Choose An Index Fund?

- - The One Fund Portfolio

- Reallocating Long Term Investments

- - Stock/Bond Reallocation

- - Rebalancing and Target Retirement Funds

- Conclusion

Firstly, What Is Long Term Investing?

Simply put, the answer is in the question, it’s investing in something for a long period of time. The long term, most would agree, would be a period of 10 years or more.

Now, that ‘something’ is really important. Not all investments are created equal. This, I think, is the big flaw with the long term investment movement. It clearly states the benefit of investing for 10 years or more. However, it is not always clear what you should be invested in for those 10 plus years.

What’s worse, in my view, is that people take the quote ‘invest for the long term’ and apply it to every finger in every pie that they have. We know that isn’t right. As I said, not all investments are created equal.

Some investments can fail. Others might only fail in terms of inflation (ie. the absolute value goes up but the relative buying power of that investment is eroded by an increase in the cost of living). The key is trying to figure out what box your investment is in. So let’s talk options.

Long Term Investing In Cash

If you’re reading this article, you’re probably aware that cash is a poor long term investment. The reason for this is inflation. When you hold cash in a bank account, you tend to (not always) earn interest. If your interest rate is less than the annual rate of inflation, your cash, in real spending terms, is losing value.

In other words, if your bank gives you 2% interest but the price of goods has gone up by 3%, you have lost spending power. If inflation didn’t exist, that would be the equivalent of your bank charging you 1% of your balance as an annual fee.

If we take the UK as an example, a measure of the rate of inflation is the consumer prices index (CPI). In December 2018, the CPI rate stood at 2%. In September 2015 the CPI rate was 0.2% and in the December of 1990 the CPI rate was a whopping 9.2%.

So to answer the question. Should you invest for the long term in cash? As a long term investment, cash is very poor. It’s rare that you’ll be able to earn enough interest on all your cash, taken as a whole, to outpace inflation. And even if you succeed year in year out, the real buying power of your money may only have increased by a tiny percentage.

Long Term Investing In Single Stocks

This, I think, is where the real danger lies with the phrase ‘invest for the long term’. There is a danger people may take the phrase and apply it to a portfolio of one or a few single stocks. In reality, the advice isn’t really applicable in this situation.

Let’s say you only ever bought 10 Apple Shares (AAPL). Let’s say you bought them back in January 2001 at their lowest price point that month. The shares would have cost $1.03 each, meaning you would have spent a grand total of $10.30.

As of January 29th, 2019, not even factoring in dividend income during that period, your investment would have grown in value to just over $1546.80. That’s a return of just over 32% per year. In this case, invest for the long term would have paid off substantially. But what if you hadn’t been so lucky.

What if instead you’d invested in Woolworth’s, Enron or Compaq. These large companies, once listed on the S&P 500 (Fortune 500), are no longer in business. ‘Investing for the long term’, in this case, is supplanted by more important advice:

‘Avoid putting all your eggs in one basket’.

Long Term Investing In Index Funds

When you google ‘invest for the long term’, it won’t take you long until you come across the phrase index funds. Index funds are effectively mutual funds which are designed to track a market index, like the S&P 500 or the FTSE 100.

Index funds are generally low cost because fund managers aren’t stock pickers, they are market matchers. Fund managers buy the constituent stocks that make up a given index in the correct proportion.

Index funds have been growing in popularity. But it is here that we run into another issue.

Which Index/Indices Should You Track?

Like picking stocks, you can run into an issue if you’re just wishing to track a market index over the long term. Which index do you pick?

When John Bogle, who sadly passed away just last month, created the first index fund in the mid-1970s, he designed it to track the S&P 500: Standard and Poor’s index of the top 500 companies by market cap listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

The S&P 500 index is filled with ‘blue chip’, large-cap companies. These are well-established companies that are considered, as a whole, financially sound. The term ‘blue chip’ has been used to describe these companies because the blue chips are the highest value chips on a poker table.

The S&P 500, from January 1988 (31 years ago) to today (31 years ago), has returned an average of around 7.8% per year. But, this is what’s known as the ‘Price Return’.

If you would have invested back in January 1988, during that 31 year time horizon you would have been accumulating dividends paid out by all of those companies. Dividends are one of the best sources of passive income. Now, instead of just taking those dividends as cash, you could have reinvested all of those dividends back into the S&P 500. This gives you the ‘Total Return’.

The ‘Total Return’ of the S&P 500, which includes reinvested dividends, has been around 10.2% per year. This means the growth of your money would have far outpaced inflation, meaning your return is substantial in ‘real terms’.

So, Why Not Invest In The S&P 500

You have to bear in mind the United States, as earth’s seat of capitalism, has outperformed other markets in recent decades. Going forward, nobody’s certain if that will continue. So what do you do now? What is your best bet? Do you invest in the US? Your home market? Somewhere else?

I discuss this in more detail in another article on home bias.

No matter which index/indices you choose to track, time, in index investing, is your friend. I couldn’t put it better than the index fund inventor himself:

“The rule for most things in life is don’t just stand there, do something…for the long term investor the rule should be don’t do something, just stand there” - John C. Bogle

How Do You Choose An Index Fund?

There are numerous index funds and ETFs which track a range of indices. So how do you choose? Here are a few things to take into account.

Fees - Index Funds are supposed to be really cheap. Don’t overpay for your index fund.

Trust - Do you trust the company you’ll be handing over your money to.

Home Bias - Are you wishing to allocate a larger proportion of your investments to domestic markets? Is this really diversification? More on that here.

Diversification - How diversified is your index? Is it diversified across sectors, currencies, company size, countries etc.

Don’t make the mistake of jumping into index trackers based on recent performance. Past performance is not indicative of future performance. You could spend your whole life trying to chase performance.

Instead, take the above factors into account and build a long term portfolio. You can always buy into more than one index fund but I personally wouldn’t overcomplicate things.

The One Fund Portfolio

In the investing world, this idea is hugely controversial. But in the index fund world, I would argue it makes complete sense, especially if you’re a young investor, who doesn’t need to hedge their bets, yet, with non-equity investments (ie. bonds). I used to own four index funds but I now only own one, a FTSE Global All-Cap Index Fund by Vanguard. I am in no way endorsed by Vanguard. I simply trust their reputation and experience.

The data above is correct as of January 31st 2019. If you’re looking skin-deep at a one-fund portfolio, you would see a 100% investment in one fund. But if you look below the surface, you can see just how diversified you are.

The FTSE Global All-Cap Index Fund is diversified across company sizes (small to large), countries (developed and emerging) and sectors (finance, technology, consumer goods etc.).

The fund, as of 31/01/19, holds 6023 stocks in 11+ sectors, across 43 countries in 6 distinct regions. An index fund has built-in diversification.

In my mind, the simpler the better. But remember…

Long Term Investing Doesn't Mean No Reallocation

The older you get, the less time you have for your investments to grow. If you’re an older investor, you may not have the ability to invest for a 30+ year time horizon. So what can you do in this case?

Stock/Bond Reallocation

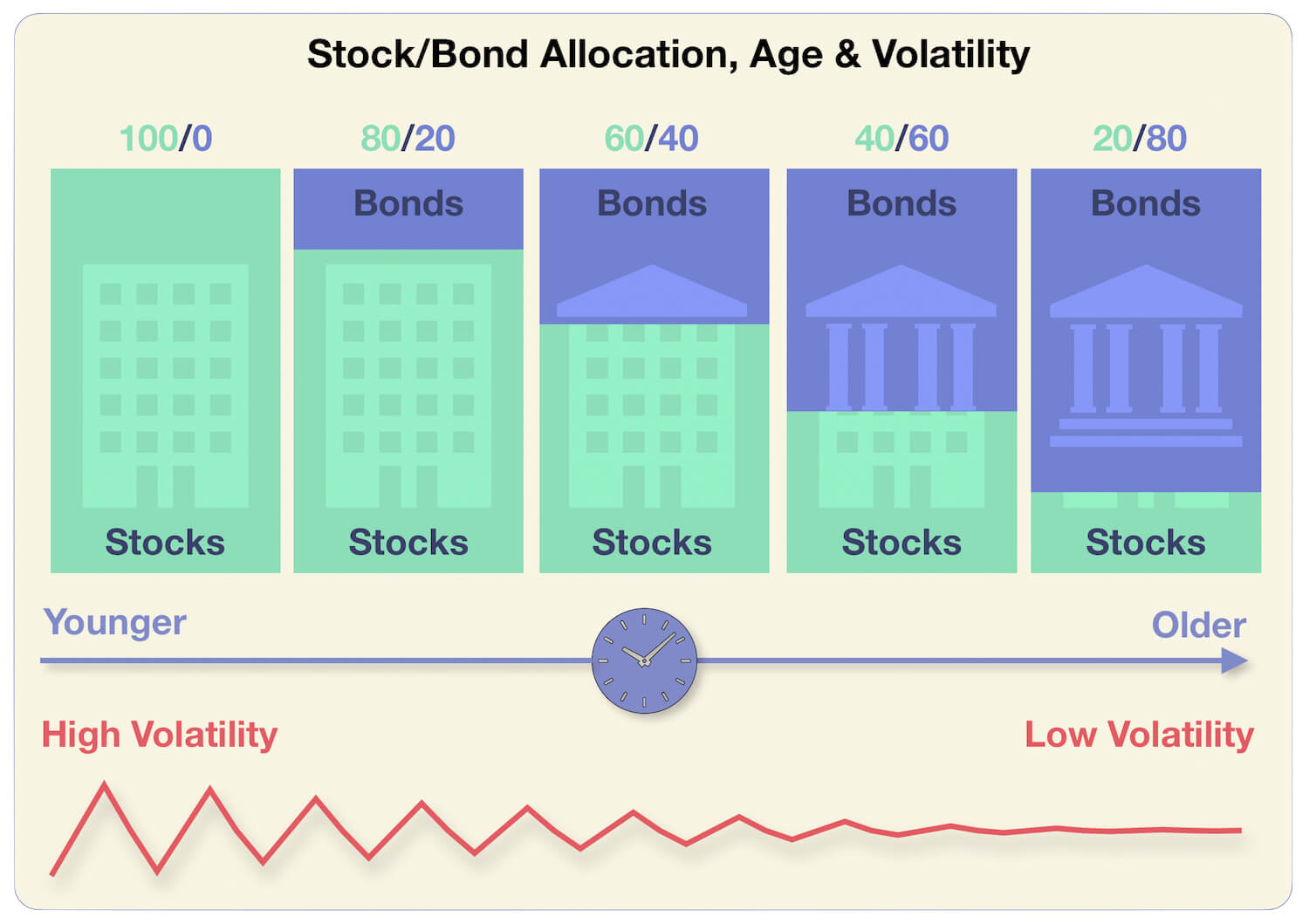

Effectively, as you age, you want your risk to decrease. You can afford to invest in volatile investments (like a stock index fund) when you’re young but when you’re an older investor, you should aim to reduce your risk and reduce the volatility of your investments. There are multiple ways to do this and I am going to focus on one in particular today. Stock/Bond Reallocation.

Bonds tend to have a very low correlation with stocks, meaning when stocks go up, bonds tend to move in the opposite direction. This means bonds are an effective way of reducing a portfolio’s volatility.

Since I am only 24 years old, I hold 100% equities (no bonds). This is because even though stocks are more volatile than bonds, they tend to perform much better than bonds over the long term. As I age, my aim is to increase the proportion of bonds in portfolio overall.

One rule of thumb which you can stick to is to hold your age in bonds.

This means if you are 40 years old, you would hold 40% of your portfolio in bonds. As you age, the relative volatility of your portfolio should decrease. It becomes less about growing your wealth and more about preserving it.

You could set a maximum at 80% bond exposure, meaning when you turn 81, you would still hold 80% of your portfolio in bonds.

Whilst I think this is a good rule of thumb, it is slightly too conservative for my tastes. I am not planning on adding any bonds to my portfolio until I’m well into my thirties.

Rebalancing and Target Retirement Funds

Of course, reallocating your portfolio away from stocks and into bonds means you will need to actually do that reallocation. You will need to rebalance your portfolio yourself, right?

Not always. Vanguard, for example, offer ‘Target Retirement’ funds.

These funds hold a portfolio of stock and bond index funds inside them. Think of it like a fund of funds. The portfolio’s are rebalanced as time goes on, away from stocks and into bonds. So if you select the Target Retirement 2065 fund, for example, you would currently be heavily weighted towards stocks. As time goes on and we get closer to 2065, the fund is rebalanced so bond index funds make up the majority of the fund.

The Vanguard ‘Target Retirement’ funds never allocate more than 80% of their portfolios to equities (stocks). Whilst that is fine for a lot of investors looking for simplicity, I would say this is a little too conservative for me.

Personally, I am going for the two-fund approach. One global equities index fund and one global bonds index fund. I don’t current buy into the bond index fund because I think I am too young (24). But when I do, I want to keep it simple. A two-fund portfolio should suffice.

Conclusion, Does Long Term Investing Work?

Yes! ‘Invest for the long term’. However, the nature of the investments you have chosen will dictate if that term applies. Cash? Watch out for inflation and poor returns above inflation. Single stocks? Make sure you’re diversified or the long term might not matter.

Index funds? I believe, one of the best bets you can make. Low fees help them outperform actively managed mutual funds. They have, if you can use the past 100 years as evidence, far outperformed both cash and fixed-income investments (especially if you reinvest dividends). And, of course, they have substantial diversification built in.

If you want to work out the projected value of your investments over a given period of time, given a projected annual return, you can use the ROI calculator on my website.

Are you invested for the long term? Or are you thinking of reallocating some of your investments, let me know your thoughts in the comments section down below. I read and reply to every comment.

If you’re looking for resources to better your own personal finances, here are some of my recommendations:

Savings/Investment Spreadsheet Downloadable - 10% of profits go to a charitable cause.

Facebook - UK Passive Investing Group - Join A Like-Minded Community

Check out my offers page to earn some free money and grab some freebies.

Rich Dad, Poor Dad by Robert Kiyosaki

The Little Book of Common Sense Investing by John C Bogle

The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham

References

Apple Shares (AAPL) - Yahoo Finance

Consumer Prices Index - Office of National Statistics

S&P 500 (^GSPC) - Yahoo Finance

Vanguard Announces The Passing of Founder John C. Bogle

The best UK free share referral offers, updated throughout April 2025. Get free stocks and shares with Shares App, FreeTrade, Stake and more.